(An Extract from ‘Gunsmoke in the park – the Paddington Rifle Range’ written by John W. Ross – May 2020)

Foreword

Firearms were widely used in colonial Australia, either by professional or volunteer soldiers, for self-defence or sport shooting. In the early years, the settlers deployed rifles to supplement their meagre diets until farming was well established. Rifle shooting was a popular pastime in the nineteenth century that most people could afford, and other entertainments were scarce. Rifle clubs and associations sprang up to organise shooting competitions and social events.

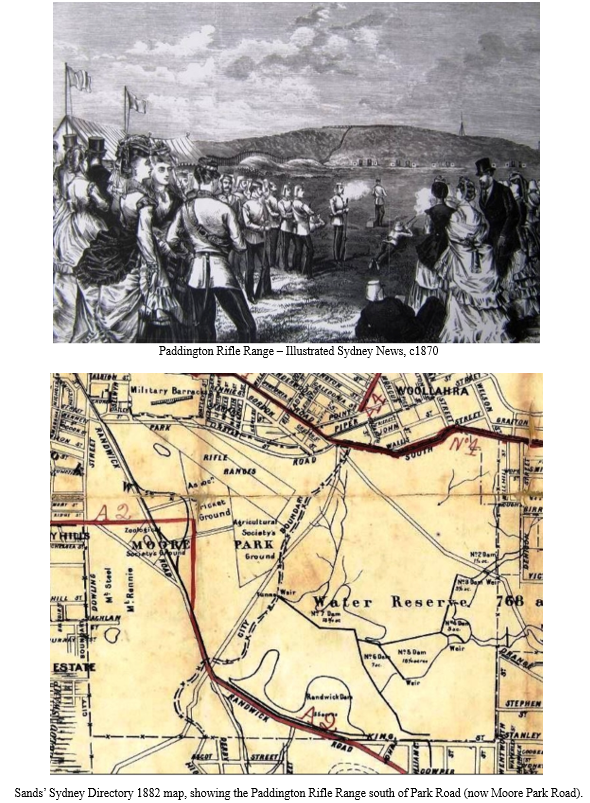

Victoria Barracks was constructed in Paddington in the 1840s as the headquarters of the British military in New South Wales. In 1852, a rifle range was established to the south of the Barracks in present-day Moore Park for musketry training and ongoing practice. A Corps of Volunteers was raised in 1854 in response to the threat of war in Europe that may have left the colonies undefended. But when the Crimean War ended a few years later, the local Volunteer movement lost momentum.

The Volunteer Corps was revived in 1860 following the escalation of the New Zealand Wars, along with a Rifle Association to organise competitions and maintain interest in the movement. A second range was constructed next to the military range in 1862, providing a home for civilian riflemen to practise their craft. The British Government withdrew its last regiment in 1870, leaving the local authorities to supply and expand the defence forces of the growing colony. By the late 1880s, the Paddington range was deemed too small for the number of infantrymen then requiring practice, and unsafe for visitors to the new Centennial Park nearby. The range closed in 1890 and was replaced by a larger rifle range at Randwick.

As the rifle range was in a prime part of the town, the State Government received several requests from organisations to use the land. The Children’s Hospital was initially allocated a site at the eastern end of the old range, but eventually built their new hospital at Camperdown. The main reuse of the land was to construct the Sydney Sports Ground, to be used for school sports during the week and a variety of other sports at the weekend, such as rugby union, cycling, athletics and motor racing. The Army established an engineers’ depot to the east of the sports field, and finally ended its long residence of the rifle range site when the Sydney Football Stadium was built in 1988.

John W. Ross

Surry Hills, Sydney

May, 2020

The Military Rifle Range

In 1851, a grant of land was given to the British Army just south of Victoria Barracks for use as a soldier’s cricket ground and a garden. The first cricket match was played in 1854[1]. The Sydney Rifle Club had been holding competitions on an informal range next to the military garden from 1851[2]. In 1852, a rifle range was constructed for musketry practice by the military, adjacent to the Military Cricket Ground and garden. Shooters fired towards the eastern end where there were sandstone formations to place targets safely[3]. The range was not fenced for some years [4], and passers-by sometimes took their chance to take a short cut across the firing area, timing their dash between tell-tale puffs of smoke from the shooting end[5].

[1] Moore Park Master Plan 2040 website.

[2] Sydney Morning Herald, 5 April 1851.

[3] Moore Park Master Plan 2040 website.

[4] Sydney Mail, 17 May 1862.

[5] Gunpowder rugby at the SCG, Saints and Heathens website.

The Volunteer Rifle Butts

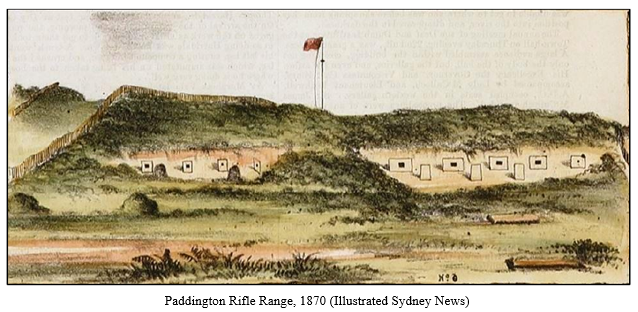

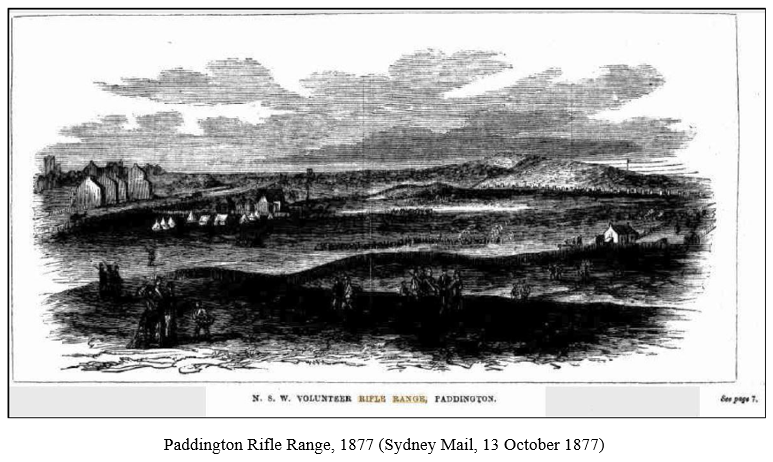

In May 1862, a new rifle range opened for the Sydney Battalion Volunteer Rifle Corps, running parallel to and south of the military range. The range was 1000 yards long and 100 yards wide, enabling two firing parties to operate simultaneously. It was generally known as the Paddington Butts or Paddington Rifle Butts.

A high rocky ridge behind the targets was covered in sand and earth to indicate the impact of any stray bullets. On either side of the range were built two bulletproof shelters (mantlets), one for the marker of points actually scored, and the other on the more westerly side for the indication of ricochets. Both the military and Volunteer ranges were fenced off, with admission through gates[6].

In 1866, the New South Wales Rifle Association held its annual prize meeting at the Paddington Rifle Range for the first time[7].

In time, military and sporting activities competed seriously for space in the area, with the rifle range operating at the same time as cricket and football matches. In 1875, a military spokesman complained that “we are driven from Moore Park by football players in winter and cricketers in summer”[8]. For their part, rugby players complained of having to play matches to the accompaniment of gunfire next door[9]. By 1871, the safety limitations of Sydney’s main rifle range at Paddington were being exposed by the firing power of the new service rifle, the Martini-Henry breech-loading rifle[10].

[6] Sydney Mail, 17 May 1862.

[7] Sydney Morning Herald, 2 October 1866.

[8] P. Derriman, The Grand Old Ground, a history of the Sydney Cricket Ground.

[9] Gunpowder rugby at the SCG, Saints and Heathens website.

[10] Kilsby, The Rifle Club Movement and Australian Defence.

In 1886, an order was issued from the Headquarters of the Military Forces that the Paddington Rifle Range be closed, as it was considered that the shooting constituted a danger to the workmen in Centennial Park. But a subsequent deputation gained permission for shooting on Saturday afternoons only, and alteration to the stop-butts enabled shooting to continue there until 1890[11].

In 1887, the Army decided that the rifle range was too small for the requirements of the growing armed forces. There was not enough room to give all the infantrymen the necessary training, especially in practice at moving targets. A larger site was selected just past Randwick, off Rainbow Street[12]. In 1888, the establishment of Centennial Park to the east of the rifle range resulted in occasional stray bullets flying overhead into the park. The range was acknowledged to be unsafe for the park users.

In March 1890, a quarryman in Centennial Park was wounded by a stray bullet from the rifle range, and the range was summarily closed by the Military authorities. This caused widespread complaints from marksmen, as no alternative range had been made available[13]. The annual prize meeting was not held by the Rifle Association that year, and The Australian Star helpfully suggested that if the riflemen went without practice for much longer, they might need larger targets when they resumed[14]. The new rifle range at Randwick was eventually opened in October 1892 for the use of troops[15].

Catering to the shooters

Firearms were a major part of early colonial life in Australia. A great number of adults (and many youngsters) owned a firearm, either as a member of a British regiment or local Volunteers and Militia, for policing, self-defence or sport shooting (game and birds). The first use of rifles and hand guns in New South Wales was to supplement the meagre diets of the convicts and settlers and for security.

From the 19th century, rifle shooting as a sport was a pastime which most people could afford, and filled an entertainment gap in the early days. But in many ways it was more than a sport, as various war scares in the nineteenth century drove the establishment of a popular Volunteer military movement with a focus on musketry[16].

[11] Kilsby, The Rifle Club Movement and Australian Defence.

[12] Sydney Morning Herald, 3 May 1887.

[13] John W. Ross, The History of Moore Park Surry Hills.

[14] Australian Star, 16 July 1890.

[15] Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate, 10 October 1892.

[16] Kilsby, The Rifle Club Movement and Australian Defence.

In common with many other popular pastimes, clubs and associations sprang up to organise competitive events and social gatherings. Gun shops were opened to supply and repair shooting equipment, and pubs were built at strategic locations to attract thirsty shooters on the way home from a hard day out on the range.

Clubs and Associations

The Sydney Rifle Club

In January 1843, an informal rifle match took place at the Red House Inn, Bedlam Ferry (near present-day Abbotsford Point), while a permanent rifle club was being planned[17]. The Sydney Rifle Club was formed soon afterwards and held its first shooting competition on Easter Monday[18]. The Club’s aim was to teach the basic skills of marksmanship to the community[19].

By 1846, the annual Easter Monday meeting was being held at the Sydney Water Reserve[20] (part of Sydney Common, probably in present-day Moore Park). In 1852, the Club was using an area near the newly-established military garden next to the Military Rifle Range[21]. Over time, the Club moved location from Paddington to Randwick (in 1890), then to Liverpool (in 1923) and finally to the Anzac Rifle Range at Malabar (in 1968)[22].

A Volunteer Small Bore Rifle Club was formed in October 1863, with the aim of keeping the Volunteers who shot with small bore rifles in practice for the next Intercolonial Rifle Match[23]. Apart from these two groups, purely civilian rifle clubs would be a rarity in New South Wales for many years. But by the time of Federation, shooting for defence purposes had grown into a large rifle club movement, spurred on by patriotism generated by the Boer War[24].

The New South Wales Rifle Association

The New South Wales Rifle Association (NSWRA) (often called the Rifle Association of New South Wales in the press) was constituted in 1860 as part of the Defence Act, to promote general rifle proficiency and to give permanency to the New South Wales Volunteer Rifle Corps[25]. Target shooting was seen as a good preparation and was popular as a patriotic pastime. Businesses and suburbs formed rifle clubs and even small towns maintained a rifle range[26].

While announcing the first shooting competition of the Association in 1861, it was acknowledged that “there was an excellent rifle club in existence, but that it was not suitable for large numbers of members, or for furthering the efficiency of the volunteer forces of the colony. The rifle association will, as do those in England and on the Continent, aid in preparation for danger from outside, and generating a spirit of self-reliance at home”[27].

[17] Sydney Morning Herald, 4 January 1843.

[18] The Australian, 24 April 1843.

[19] Sydney Rifle Club website.

[20] Bell’s Life in Sydney, 11 April 1846.

[21] Sydney Morning Herald, 2 October 1852.

[22] Sydney Rifle Club website.

[23] Sydney Morning Herald, 31 October 1863.

[24] Kilsby, The Rifle Club Movement and Australian Defence.

[25] History, Roseville Rifle Club website.

[26] Museums Victoria Collections website.

[27] Sydney Morning Herald, 13 May 1861.

Leadership of the rifle associations came from the top levels of society from every field: judicial, political and administrative. Generally, businessmen and Catholics were not prominent in leadership of the associations, although this gradually changed as rifle shooting became one of the most popular pastimes of the people, albeit cloaked in patriotism. The first president of the NSWRA was Sir William Montagu Manning, Scottish-born barrister and politician, who held the position for 35 years until his death in 1895.

The first match in September 1861 at Randwick racecourse, courtesy of the Australian Jockey Club which was paid a third of the takings, was a moderate success. The Sydney Battalion of Volunteers had prepared the firing range by clearing scrub and constructing booths for the spectators. They also acted as scorers and markers during the competition, as well as supplying some of the competitors[28]. The first match over 300, 500 and 600 yards, was contested for prizes of twelve rifles valued at £247 as follows:

- Two Whitworth rifles.

- Two Westly Richards breech-loading rifles.

- Two Westly Richards carbines.

- One Thomas Wilson breech-loading patent rifle.

- One Lancaster rifle.

- One sea service prize rifle.

- One rifle corps rifle.

- One General Hay’s pattern rifle.

- One long Enfield rifle.

The second match was for the Silver Cup of the Association, valued at £50, to be shot over distances of 700, 800 and 900 yards, and was open to the winners of the twelve rifles in the first match. Only enlisted Volunteers could compete in the first two matches, using any Government pattern rifle. Third and fourth matches were contested for cash prizes[29]. As rifle shooting at the Randwick racecourse was completely unregulated, there was constant danger to passing pedestrians and animals from stray bullets and ricochets[30]. The NSWRA continued to hold its meetings there until moving to the Paddington Rifle Range in 1866[31].

The two colonies, New South Wales and Victoria, were even then highly competitive: New South Wales had the larger population with more established industry, whereas Victoria had gold and saw itself as more progressive. So it was not long before they found a new outlet for their rivalry by organising the first Intercolonial Rifle Match for small-bore rifles (calibre less than 0.577”) in 1862 for a Challenge Shield[32]. The New South Wales team members used an assortment of Whitworth, Kerr, Alexander Henry and Turner rifles, which were all percussion cap muzzle-loaders at 0.451” calibre[33].

[28] Kilsby, The Rifle Club Movement and Australian Defence.

[29] Sydney Morning Herald, 10 May 1861.

[30] Kilsby, The Rifle Club Movement and Australian Defence.

[31] Sydney Morning Herald, 2 October 1866.

[32] Kilsby, The Rifle Club Movement and Australian Defence.

[33] History, New South Wales Rifle Association website.

The competition was held in November 1862 at the Sandridge Butts in Melbourne (in present-day Port Melbourne) between the ten best shots from the respective colonial Volunteer Corps. The New South Wales sharp-shooters were victorious in the inaugural competition.

The most memorable part of the trip south occurred on the way back to Sydney, when the steamship City of Sydney, with the whole New South Wales team on board, ran aground on rocks near Green Cape late at night in heavy fog. All 100 passengers and crew were taken to safety in life boats, but six of the ten rifles used by the Volunteers in the Intercolonial match were lost. Two rifles were retrieved from the lower deck by their owners, who risked their lives to go back for them before jumping into a departing boat. The remaining two only survived because they were inadvertently left behind in the hotel in Melbourne by two members of the contingent[34].

The annual matches were keenly contested and very popular with the public. Press reports noted a steady improvement in scores each year[35]. After seven annual competitions, held in alternating years at Sydney and Melbourne, New South Wales won perpetual ownership of the cup in 1867 by three victories in a row. Intercolonial shooting contests then lapsed until 1873, mainly because of financial and administrative problems within the Victorian Rifle Association[36].

The NSWRA continues to run shooting prize meetings through the State, including at the Sydney shooting ranges at Hornsby and Malabar[37].

Note: John Ross approved the publication of this article in an email to Bruce Scott on 26 January 2025 advising he wrote it as a history topic really for educational purposes, and the more people that read it the better.

It is acknowledged that this article is an extract from ‘Gunsmoke in the park – the Paddington Rifle Range’ which can be accessed at https://shazbeige.com/pdf/Paddington_Rifle_Range.pdf

[34] The Newcastle Chronicle, 12 November 1862.

[35] Sydney Morning Herald, 19 December 1865.

[36] Kilsby, The Rifle Club Movement and Australian Defence.

[37] New South Wales Rifle Association website.

References

Sands’ Sydney Directories, 1858 – 1933.

City of Sydney Rate Assessment Books, 1845 – 1948.

State Heritage Register, Office of Environment and Heritage, New South Wales Government, website

http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/heritagesearch.aspx

National Library of Australia – Trove digitised newspaper archive, 1803 to 1955.

Archives, City of Sydney website http://archives.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/

John W. Ross, The History of Moore Park Surry Hills, 2018, Sydney.

Australian Colonial Gunsmiths and Ironmongers, The Firearms Technology Museum website, www.firearmsmuseum.org.au

Sydney Rifle Club website, www.sydneyrifleclub.org

History, New South Wales Rifle Association website, https://www.nswra.org.au/pages/history

Museums Victoria Collections website, https://collections.museumvictoria.com.au

Some History, Roseville Rifle Club website, https://rosevillerc.com

Andrew Kilsby, The Rifle Club Movement and Australian Defence 1860-1941, UNSW, Sydney, 2014.

Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences website, https://collection.maas.museum

The British Army in Australia, Digger History website, www.diggerhistory.info

Military system in Australia prior to Federation, Australian Bureau of Statistics website, www.abs.gov.au

Citizen soldiers, Sydney Living Museums website, www.sydneylivingmuseums.com.au

Moore Park Master Plan 2040, Appendix 2 – Heritage Analysis, http://moorepark.sydney/wp-content/themes/mooreparkmaps/pdf/A2-heritage.pdf

John Mordike, The Origins of Australia’s Army: the Imperial and National Priorities, Australian Defence Force Journal, March/April 1991.